Resistance Cartography

I’m launching this blog to have a home online for my writing and research about the intersection of counter-mapping and spatial theory in contemporary art. I am interested in the urban geology of lands being built on top of older lands, and I’m interested as an artist in exploring these sedimentary layers of maps laid on top of older maps to poke holes in the official narratives of power in American life and especially in American cities. I never stop being surprised by the power that maps and archival documents have to excavate truths from the whitewashing of official histories and fading collective memory. Maps are such profound vehicles for societal commentary and change. They’re not just tools for spatial orientation. Counter-mapping artistic practices serve as forms of resistance, reimagining and reclaiming spaces and histories.

I will open with a terrific literary forgery:

Of Exactitude in Science

…In that Empire, the craft of Cartography attained such Perfection that the Map of a Single province covered the space of an entire City, and the Map of the Empire itself an entire Province. In the course of Time, these Extensive maps were found somehow wanting, and so the College of Cartographers evolved a Map of the Empire that was of the same Scale as the Empire and that coincided with it point for point. Less attentive to the Study of Cartography, succeeding Generations came to judge a map of such Magnitude cumbersome, and, not without Irreverence, they abandoned it to the Rigours of sun and Rain. In the western Deserts, tattered Fragments of the Map are still to be found, Sheltering an occasional Beast or beggar; in the whole Nation, no other relic is left of the Discipline of Geography.

From Travels of Praiseworthy Men (1658) by J. A. Suarez Miranda

Argentine poet Jorge Luis Borges’s famous 1946 Of Exactitude in Science purports to be a found scrap of a 17th century text claiming that the craft of cartography once reached such perfection that the map of the Empire itself covered an entire Province. This canard has become one of the foundational metaphors for exploring the map-territory relation. Just as René Magritte’s 1929 painting of a pipe is by itself n’est pas une pipe,

a map by itself is not proof of received truths in geography, it is a symbol of humankind’s never ending struggle to stake claims to land on a seemingly ever-shrinking planet. Borges imagines an empire where the science of cartography becomes so exact that only a map on the same scale as the empire itself will suffice. Jean Baudrillard cited the story by Borges as the "finest allegory of simulation" in his critique of modern society, Simulacra and Simulation, describing how "a double ends up being confused with the real thing." Baudrillard used this allegory (and scrambled generations of teenage mindsand to propose that hyperreal simulations have supplanted reality, creating a world where representations do not just reflect reality but become reality themselves. The map (simulation) precedes and determines the territory (reality), leading to a situation where the real and the imaginary cease to be distinguishable. The Borges story draws on Lewis Carroll’s 1893 Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, a humorous yarn of cartographers gone wild, drawing a map at a perfect 1:1 scale so unwieldy and large that it was never unrolled and used. Later Umberto Eco drew upon the work in a short story, "On the Impossibility of Drawing a Map of the Empire on a Scale of 1 to 1." This fundamental trade-off between accuracy and usability of a map is known as Bonini's paradox, "Everything too simple is false. Everything too complex is unusable."

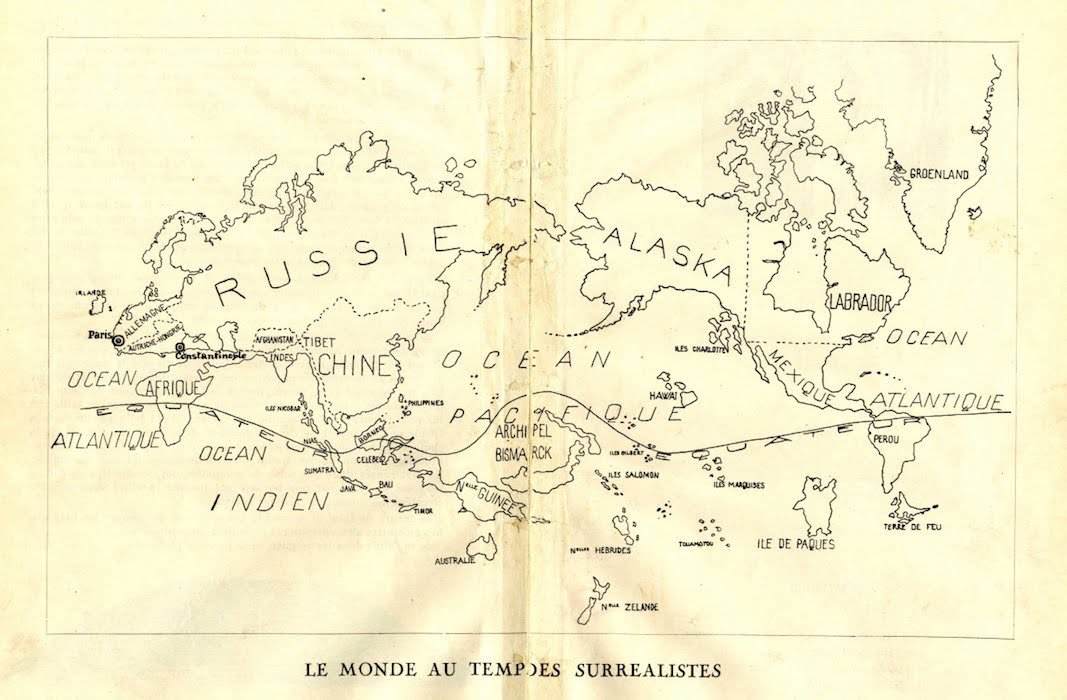

Between the false and the unusable lies the vast gray area of cartography, a pseudoscience that has long been a battlefield for humankind’s carving out of territory through the demarcation of a complex, multidimensional world with finite land resources. This gray area has proven fertile territory for artists over the past century, a cascade of critical art cartography initiated by The Surrealist Map of 1929, created by Paul Éluard for the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme held in Paris that year. The fascinating Surrealist Map radically reimagined the world's geography to reflect the group's disdain for conventional political and cultural boundaries:

Paul Éluard, Le Monde Au Tempes Surrealistes

The Pacific Ocean is centered on this map, rather than the expected Atlantic, metaphorically exiling Europe to the end of the earth and subverting the cartographic hegemony of the world order while a ballooned Russia celebrates the still-fresh news of the Bolshevik revolution.

By exploring the relationship between maps and landscapes through the lens of critical cartography, contemporary art, and spatial theory, this thesis endeavors to use spatial theory to examine the metaphorical, geopolitical, and imaginary capacities of maps. I propose that cartography is not just as a tool for geographical orientation but also a profound medium for artistic expression, political critique, and radical thought. The research explores some strands of the artistic attempts to decolonize perceptions and narratives of space and place. These themes are set out through examples drawn from a set of contemporary artists whose work has incorporated themes of mapping and spatial theory in order to explore countercultural narratives. In upcoming posts, I plan to consider three ways that artists in recent decades have found maps to be fertile territory for imagination and subversive challenges to power structures:

1. Embodied Cartographies: The act of traversing landscapes transcends mere physical movement, becoming a conduit for understanding and disrupting spatial narratives. The act of walking embodies a form of counter-mapping that challenges and redefines boundaries. I will show ways that movement through space can interrogate and illuminate the layers of history, conflict, and memory inscribed upon the landscape. Such embodied cartographies reveal the potency of human presence and movement as tools for spatial reclamation, engaging directly with the politics of place and the tactile realities of geography. As artists navigate these contested spaces, their paths forge new maps imbued with the complexities of human experience ungraspable from the simulacra of any lesser-scale cartographic representation. Further, these map/walks enable the practice of participatory psychogeography, facilitating a viewer to walk in the footsteps of the artist to draw their own conclusions regarding complex social and psychological landscapes.

2. Aerial Landscapes Employed to Represent Spatial Relationships. A bird's eye view is not primarily a tool for navigation but can serve as a potent metaphor for abstract concepts, including as symbols of entropy and change illustrating the transient and evolving nature of landscapes. Maps are often used as representations of human impact on the Earth, emphasizing social upheaval, ecological catastrophe, and proof of covert military actions.

3. Critical Cartography. There has long been a dynamic interplay between borders, political instability, and artistic representation. Maps both mirror and influence geopolitical shifts, drawing attention to territorial disputes and alterations. Artists engage with maps as a medium to critique and shed light on these changes, and depict boundaries transformed, destroyed, or erased by political, environmental, or social forces. This form of map challenges the perceived neutrality of mapping, unveiling the inherent biases and power structures embedded within traditional cartographic practices. It highlights the erasure of indigenous maps and cartographic traditions through colonial practices, advocating for the creation of alternative or counter-maps. This critical approach to cartography seeks to recognize and restore the value of marginalized perspectives, offering a pathway towards a more inclusive understanding of space and place.