On LaToya Ruby Frazier

In 2018, The Atlantic Magazine chartered a helicopter and flew photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier to rephotograph scenes from Chicago, Memphis, and Baltimore where protests, riots, and memorials during the aftermath of the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led to physical urban changes visible a half century later.

What a Picture from the Sky Reveals About Oppression, The Atlantic (2018)

Frazier taps into aerial photography’s uncanny power to allow the viewer to become disoriented in time and more easily visualize the disruptions of past eras. Chartering a flight over Chicago, Frazier documented scenes where in 1968, Mayor Richard J. Daley chose to stifle unrest after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination with a notorious order for police to “shoot to kill arsonists and shoot to maim looters.” The Atlantic wrote about how the structural inequality of Chicago has scarcely diminished even with the demolition and redevelopment of the notorious Cabrini-Green public housing project seen in Frazier’s image below. Frazier documented scenes where the Chicago police mobilized in response to escalating violence in Black neighborhoods, which included peaceful school walkouts as well as widespread window-breaking, looting, and arson.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Geography of Oppression: Chicago (2018)

Reports of sniping from buildings added to the tension, prompting armed responses from law enforcement. The upheaval left the city grappling with the tasks of rebuilding and addressing deep-rooted community grievances, all while under the shadow of a fractured trust between the Black community and city authorities.

Luigi Mendicino/Chicago Tribune (1968) and Google Earth (2024)

animation by Joel Silverman

As a demonstration of Frazier’s thesis, I have taken Chicago Tribune photojournalist Luigi Mendicino’s April 6, 1968 photograph of the 3000 block of West Madison Street, Chicago showing the destruction of the block in the paroxysm of violence and despair after the MLK assassination, and overlaid it with a 2024 Google Earth view showing how the formerly grand block now stands empty and decrepit. Assassin James Earl Ray’s bullet changed the mapped landscape in a way that is visible from space over half a century later. The day after King’s death, poet Nikki Giovanni considered America’s burned inner cities in her masterpiece of anguish, Reflections on April 4, 1968:

Let america's baptism be fire this time. Any

comic book can tell you if you fill a room with combustible

materials then close it up tight it will catch fire. This is a

thirsty fire they have created. It will not be squelched until it

destroys them. Such is the nature of revolution.

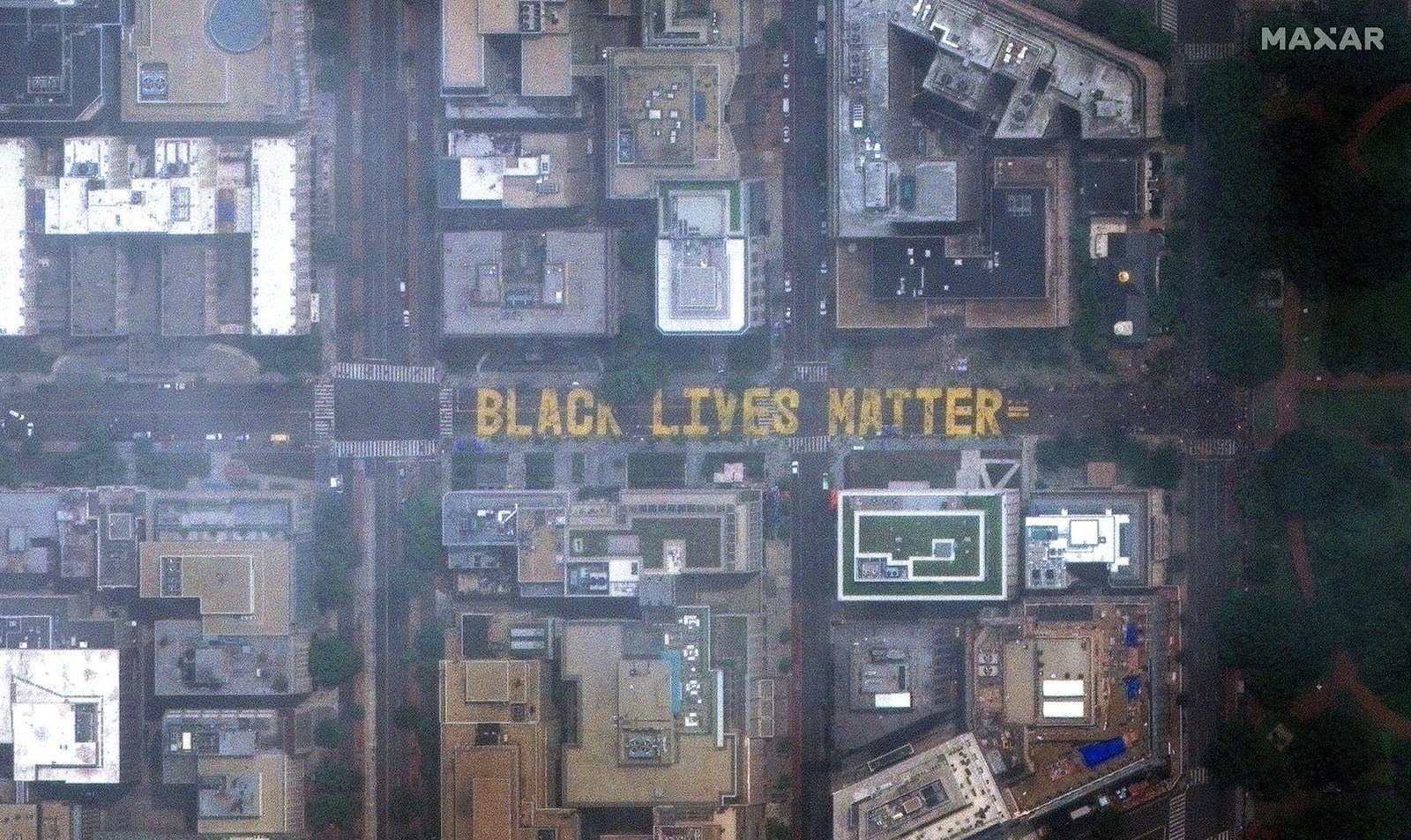

Frazier made her Atlantic Magazine flight in the aftermath of the 2015 and 2016 killings by police officers of Freddie Gray, Alton Sterling, and Philando Castile, and her photo series was fresh in my mind when the 2020 police killing of George Floyd brought as many as 26 million protestors to the streets in U.S. cities. Mindful of the power of aerial photography, on June 5, 2020, the DC Public Works Department painted the words "Black Lives Matter" in 35-foot-tall yellow capital letters on 16th Street near the White House. In subsequent months, artists in more than 85 other cities also painted Black Lives Matter road murals across the United States, acts of dissent against police state violence visible from satellites and some of them for a time visible in Google Earth, thus literally becoming part of the global map.

Maxar Technologies satellite view of Washington DC mural, June 6, 2020

There is a rich tradition in contemporary art discourse of using maps as metaphors of entropy and change, of engagement with urban spaces, of the traces humans make on the landscape, of the organization of spatial information and of social relationships. Maps have been assumed for millennia to be empirical truths, but when maps are read critically as texts, it quickly becomes evident that cartography is an uncertain science, as boundaries are fluid and map projections inherently contain political and colonial assumptions. Think of the earth sitting at the center of the universe before the Copernican revolution, or the United States appearing so frequently at the center of modern Western maps, as critiqued by Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion map of Spaceship Earth.

Buckminster Fuller, Dymaxion World Map (1980)

Frazier, like Sol LeWitt before her, reveals that maps are not merely tools for spatial orientation but are also profound vehicles for commentary and change. Artists like these challenge the traditional expectations embedded in cartography, transforming the idea of mapping into dynamic frameworks for understanding and questioning the world. They not only depict geographical realities but also challenge the underlying power structures. This conception of maps allows artist/cartographers to be not just navigators of physical spaces, but navigators of societal change, steering public discourse through a visual unveiling of the world's hidden narratives and power dynamics.